News Today

A Historical Analysis With References, Context, and Archival Moments- by Jeremiah Nome

For decades, Nigeria’s political stability rested on one quiet, unspoken strategy:

Keep the South divided.

A united Southern front, one where the South-East, South-South, and south west, acted as a strategic block has always been the single greatest fear of Nigeria’s ruling elites. It threatened the balance of power, the control of resources, and the political architecture that kept the centre dominant since 1966.

This article traces the history, the politics, and the hidden reasons why southern unity was, and still is one of the most powerful forces in Nigerian politics.

The Foundation of Federal Power Was Built on Division

When Nigeria adopted a highly centralized system after the civil war, the military government created a structure that weakened regional alliances. States were carved up in ways that diluted old regional blocs (East, West, North) and replaced them with small, dependent units. Why?

Because regional unity means bargaining power, and bargaining power threatens the centre.

A united South, controlling the ports, the oil, the Atlantic coastline, and the nation’s commercial capital (Lagos) would have been too strong.

So fragmentation was the strategy.

early federalism and the principle of derivation

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Nigeria’s regions had significant autonomy. Revenue allocation relied heavily on the principle of derivation meaning regions kept a substantial share of the revenue from resources produced in their territories (cocoa in the West, groundnuts in the North, palm produce in the East, etc.).

https://www.forumfed.org/document/federal-republic-of-nigeria/

A key study of Nigeria’s fiscal history notes that derivation was the dominant revenue principle in the 1950s and 1960s, and powerful blocs fought hard to protect it because it rewarded productivity and regional control over resources.

https://www.forumfed.org/document/federal-republic-of-nigeria/

This older model is exactly what many southern actors today mean when they talk about “true federalism”:

The idea that regions or states should control their resources, pay a clearly defined share to the centre, and develop at their own pace.

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1429323/a-new-nigeria-is-possible-but-those-opposed-to.html

Military rule and the death of genuine federalism

The coups of 1966, the civil war (1967–70), and decades of military rule radically changed this balance. Scholars of Nigerian federalism point out that political and fiscal power became heavily centralised, especially from the late 1960s onward.

https://www.pluralism.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Nigeria_EN.pdf

Key things happened:

- Creation of more states under military governments, breaking the old regions into smaller, weaker units dependent on the centre. https://www.forumfed.org/document/nigeria-over-centralization-after-decades-of-military-rule/

- Dina Commission (1968) and other reforms drastically reduced derivation as a revenue principle, shifting money to the federal level and joint state accounts. Dialnet

- Nationalisation of oil and control of mineral resources, consolidating ownership in the federal government rather than in regions or communities. Horizon

By 1999, as one federalism study puts it, Nigeria had become a “highly centralised federal state”, where the national government controlled most key powers and resources. Council on Foreign Relations

In simple terms; The military took a federation designed to balance powerful regions and turned it into a centralised system where whoever controlled Abuja controlled almost everything.

That is the structure southern unity threatens.

Oil, Land and the Southern Grievance

a) Oil wealth, southern poverty

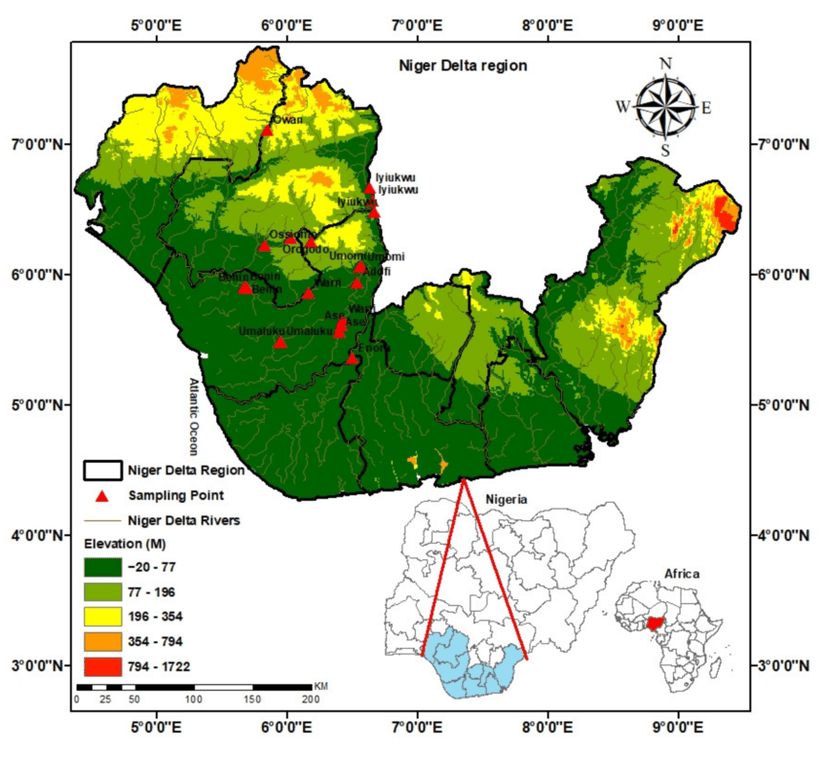

Crude oil – located overwhelmingly in the South-South/Niger Delta – became the lifeblood of Nigeria’s economy, contributing over 80% of foreign exchange and a major share of government revenue for decades. ResearchGate

Yet, research on the Niger Delta repeatedly shows a grim paradox: the region that provides the bulk of Nigeria’s oil revenue is among the most environmentally damaged and economically deprived, with high poverty and underdevelopment. ResearchGate

b) From 50% derivation to 1.5–3%, then 13%

Before the oil boom, producing regions could enjoy up to 50% derivation on key commodities. After oil took over and power was centralised, derivation for oil fell to 1.5–3% for much of the military era, rising only to 13% after fierce agitation in the early 2000s. Pearl Research Journals

Accounts of this struggle credit Obong Victor Attah (then governor of Akwa Ibom) and other Niger Delta governors for pushing a coordinated demand for resource control, forcing the federal government to accept the 13% derivation compromise. 3IIARD Journals

Even pro-federal scholars admit;

The derivation principle has been the main bone of contention in Nigeria’s intergovernmental revenue relations since the discovery of oil. Sryahwa Publications

c) Land Use Act and the dispossession problem

The Land Use Act of 1978 vested all land in each state in the hands of the governor, “in trust” for the people, radically altering traditional land ownership and limiting community control. faolex

Together with the Petroleum Act (which vests all petroleum resources in the federal state), this framework means communities in oil-producing areas bear the environmental cost but have almost no legal control over the resources under their land. rsupubliclawjournal

Southern agitation is therefore not just emotional; it’s grounded in legal and fiscal structures that many see as unjust – and that a united South seeks to renegotiate.

3. The Rise of Southern Unity: Governors, Elders and Movements

a) The Southern Governors’ Forum (from 2000/2001)

The modern phase of “southern unity” is often traced to the Southern Governors’ meetings that began in Lagos (October 2000) and continued in Enugu in January 2001.

At Enugu in January 2001, the governors jointly declared that resource control and derivation should guide revenue allocation going forward, explicitly tying their stance to true federalism. IJSS

Subsequent southern summits (e.g., Port Harcourt 2004) continued to push for: allAfrica.com

- Resource control

- Devolution of powers

- Stronger derivation

- A restructured federation

This was the first time in the Fourth Republic that elected governors from South-east, and South-South coordinated so openly against the centre on fiscal and constitutional questions.

b) Socio-cultural blocs: Ohanaeze, PANDEF, SMBLF

Parallel to the governors, socio-cultural groups in the South and Middle Belt, Ohanaeze Ndigbo, PANDEF (Pan-Niger Delta Forum), Middle Belt Forum — repeatedly issued joint communiqués calling for:

- Restructuring

- Devolution of powers

- Regional or state control of resources

- Implementation of the 2014 National Conference report

These organisations have explicitly framed restructuring as a return to what Nigeria’s founding leaders originally negotiated – a less centralised federal system based on regional autonomy and derivation.

c) The Asaba Declaration (2021): A modern shockwave

On 11 May 2021, all 17 Southern governors met in Asaba, Delta State, and issued the Asaba Declaration, a bold 11-point communiqué. Key points included: Wikipedia

- Commitment to Nigerian unity “on the basis of justice, fairness and equity”

- Ban on open grazing across the South

- Call for state police and restructuring

- Demand for a review of the revenue allocation formula in favour of sub-national governments

- Call for a national dialogue to address widespread agitations

The reaction from key northern and federal actors was furious:

- The Attorney-General, Abubakar Malami, called the open-grazing ban “unconstitutional”, comparing it to northern states banning spare parts trade. PlacNG

- The Presidency described the decision as “legally questionable” and accused southern governors of playing politics. Energy Focus Report

- Miyetti Allah, a herders’ group, called it “a declaration of war” and even “a call for secession”. Wikipedia

In other words, a regional communiqué that combined security, land use and restructuring instantly triggered national anxiety among those who benefit from the current centralised order.

4. Why Southern Unity is So Threatening to Nigerian Elites

Now to the core question: why does this unity terrify political elites, especially those anchored in the current power structure?

We can break it down into several overlapping fears.

4.1. Fear of losing control over revenue and patronage

Nigeria’s central government still controls:

- Ownership of petroleum resources and most solid minerals rsupubliclawjournal

- A large federation account whose distribution formula heavily shapes which states thrive

- Critical levers like security, ports, customs, major infrastructure and key agencies

Studies show that oil revenue has long formed the bulk of government income (even if oil is now a smaller share of GDP itself), which makes control of oil-related revenue a massive patronage tool. ResearchGate

A united South asking for:

- Higher derivation (more than 13%)

- Resource control (states/regions managing oil and paying tax to the centre)

- Constitutional guarantees that protect these rights

…directly threatens the fiscal dominance of Abuja and the power of elites whose political survival depends on distributing federal largesse to their networks. Sryahwa Publications

Simply put:

If the South controls more of its oil, gas, ports and internal revenues, Abuja’s leverage shrinks – and with it, the bargaining power of many entrenched political actors.

4.2. Fear of an economic and demographic bloc

The South is not just oil. It also has:

- Some of Nigeria’s largest urban economies (Lagos, Port Harcourt, Onitsha, Aba, Ibadan, etc.)

- Major ports and trade routes

- A huge share of manufacturing, finance, services and tech

Add the South-South (oil and gas) and South-East (commerce, industry, diaspora-driven investment), and you get a formidable economic bloc. When these zones act together politically, they can:

- Negotiate from strength

- Coordinate policies (e.g., on open grazing, internal security, taxation, power generation)

- Influence national debates on restructuring and revenue allocation

For elites whose power has been built on balancing and fragmenting regions, the prospect of a coherent, assertive southern bloc is understandably unsettling.

4.3. Fear of dismantling “unitary federalism”

Since 1966, every constitution has entrenched an increasingly long Exclusive Legislative List — areas where only the federal government can legislate (e.g., policing, minerals, ports, rail, major taxation). Analysts describe this as a drift towards “unitary federalism”. Council on Foreign Relations

Southern unity – whether via governors’ forums or SMBLF communiqués – consistently targets this exact architecture:

- They call for state police

- Demand devolution of powers from the Exclusive to the Concurrent/Residual lists

- Push for fiscal federalism — more control of locally generated revenues

A bloc that can coordinate legislation, litigation and political negotiation across 17 states increases the odds that these demands will eventually be realised. For those invested in the centralised status quo, that’s a direct threat.

4.4. Fear that old divide-and-rule tactics will fail

Historically, Nigerian politics has often pitted:

- Majority southern groups against each other (Yoruba vs Igbo, minorities vs “majorities”, etc.)

- Niger Delta vs “core South-East”,

- South vs Middle Belt, and so on

Scholars on group inequalities argue that the combination of colonial legacies, regional rivalries and manipulated census figures created an arena where elites survive by playing regions against each other, rather than by building inclusive national coalitions. Global Centre for Pluralism

Southern unity – particularly when it includes the Middle Belt through SMBLF – threatens to collapse these manufactured divisions, replacing them with a broad coalition around shared issues:

- Security

- Resource control

- Restructuring

- Fair appointments and political representation

If that coalition were to solidify and stay disciplined, it could force constitutional changes that decades of solo agitation failed to achieve. That is the real nightmare scenario for elites who rely on fragmentation as a political strategy.

4.5. Fear of a precedent for other regions

If the South successfully negotiates:

- Stronger derivation

- State police

- Greater control over resources and taxation

…it sets a template other regions can copy:

- Middle Belt states could push for more control over solid minerals and land.

- Northern minorities might demand regional governments that shield them from domination by larger northern blocs. voiceoflibertyng.com

So when elites resist southern unity, they are often pre-empting a chain reaction that could produce a much more decentralised federation than they are comfortable with.

How the Fear Shows Itself: The Reaction to Asaba & Beyond

We don’t have to guess elite fears; we can literally read them off their reactions.

- After the Asaba Declaration, the Attorney-General, Presidency, key senators and northern interest groups all rushed to frame the move as:

- Unconstitutional

- A threat to national unity

- A disguised secessionist move Wikipedia

- Miyetti Allah’s description of the declaration as “a declaration of war” and “call for secession” shows how southern coordination on even one policy area (grazing) is interpreted through a security lens, not just a legal or economic one. Wikipedia

- Media coverage and editorials from 2021 onwards kept returning to the question: is this still federalism, or is it a return to regionalism that might break the federation? ThisDayLive

In 2023–2024, SMBLF statements to President Tinubu repeated the core themes:

- Implement restructuring and true federalism

- Address perceived marginalisation in appointments and state creation

- Consider the release of Nnamdi Kanu as part of political de-escalation Tat Live+3The Guardian Nigeria+3Vanguard News+3

The fact that these communiqués continue to generate strong responses shows that the fault line has not gone away – it’s just evolving with new administrations.

The Weaknesses Inside Southern Unity (And Why Elites Bet on Them)

It’s important to note that southern unity itself is not perfect or automatic. Commentators and activists often highlight:

- Elite ambivalence – some southern politicians have historically aligned with northern power brokers whenever it suits their personal ambitions, weakening collective bargaining.

- Internal contradictions – for example, different visions of restructuring (regional vs. state-based; 6 zones vs. 12 states), and different calculations over presidency rotation.

This inconsistency is part of why entrenched elites feel they can outlast or divide southern coalitions. But the pattern is clear:

- Each time the South manages to act together for a sustained period, it forces concessions (e.g., 13% derivation; partial movement on anti-open-grazing laws; serious national debate on restructuring). Pearl Research Journals

So the fear is not imaginary. It is grounded in what southern unity has already achieved, and what it could achieve if it became more disciplined and long-term.

Conclusion: Southern Unity as a Mirror of Nigeria’s Unfinished Project

“Why did southern unity terrify Nigeria’s political elites?”

Because it challenges the post-1966 bargain on which many of them built their careers:

- A centralised state that controls oil and minerals

- A fiscal system where derivation is small and Abuja is king

- A security architecture centrally controlled and usable for political purposes

- A political culture where elites survive by playing regions and ethnic groups against one another

When the South – and increasingly, the South plus Middle Belt – coordinate their demands, they expose just how fragile that bargain is. They remind the country that Nigeria once experimented with a more genuinely federal system, where regions kept more of what they produced and had greater autonomy.

Whether one agrees with every tactic or communiqué, it’s hard to deny this:

Southern unity forces Nigeria to confront questions it has postponed since independence — about who owns resources, who controls security, and what kind of federation the country wants to be.

That is why it terrifies some elites. And that is also why it keeps returning, in different forms, each time the system reaches another breaking point.